Skeleton Tracking and IK Based Teleoperation of a 14 DoF Dual Arm Manipulator

Master’s Independent Project, Winter 2016 | Advisor: Dr. Jarvis Schultz

Objective and Motivation

Enable a human user to remotely and intuitively operate a human-like robot’s arms. Use its strong and precise appendages, but rely on our own advanced brains to decide the best way to manipulate objects in the robot’s world. If this technology is perfected, it will have diverse applications such as remote bomb disposal, complex manipulation tasks in outer space, telesurgery, and human-machine interaces.

Status

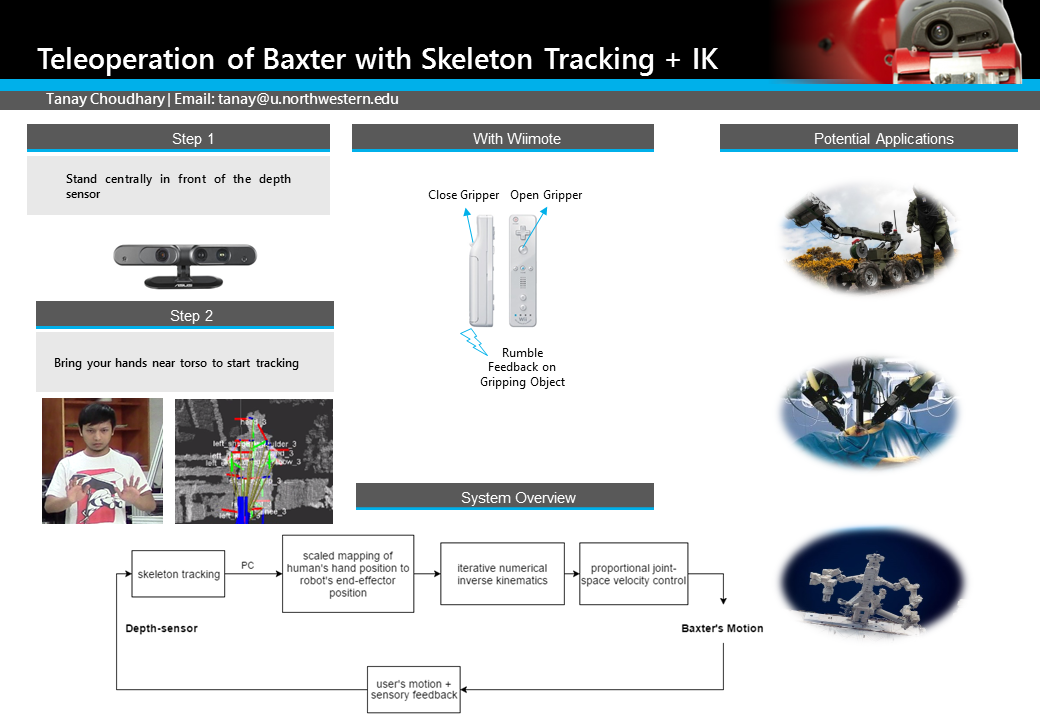

Using a depth sensor, Baxter is successfully shadowing its human user’s arm motions, and is able to pick and place objects within its workspace via a Wiimote held by the user, which additionally provides haptic feedback for the task.

Usage

The following packages are pre-requisites, in addition to the Baxter SDK and the NITE skeleton tracking library:

- skeletontracker_nu

- skeletonmsgs_nu

- Optionally, if you want control over gripper and haptic (vibration) feedback, wiimote

After enabling Baxter, simply roslaunch baxter_skeletonteleop.launch to start the program. You should soon see an RViz window with the depth video overlaid on the skeleton tracker. Stand in front of your OpenNI-compliant depth-sensor (such as Kinect or Asus Xtion), and bring your hands to the start position (both hands near the torso) to begin tele-operating the robot. If there are multiple people coming in and out of the depth sensor’s field of view, Baxter will track whichever user is most central.

If you’re holding your paired Wiimote, press the B button to close Baxter’s gripper (currently only one arm supported for gripping) and the A button to open it. If Baxter grabs an object, the Wiimote would momentarily rumble for user feedback. To keep the end-effector’s default orientation (facing you), use the Wiimote horizontally; to switch to facing down orientation (maybe for picking something off a table), use it vertically.

The robot’s joint speeds are intentionally capped to 30% of maximum, as a safety precaution. The current scaling factors for mapping human hand position to Baxter’s end-effector position work pretty well for most people in my experiments, but one may need to tweak them if that isn’t the case. This will also be necessary if your depth sensor’s coordinate axes are different from mine (I’m using an Asus Xtion Pro Live).

Implementation

The system is implemented in ROS, with the following broad flow of processes:

An object-oriented structure was adopted for the package; it has one main (node) script,teleop.py, and two dependent modules limb_mover and ik_solver. Inverse kinematics was selected as the teleoperation approach instead of geometry mapping based forward kinematics because numerous papers have shown that the former produces more reliable motions. It is also the pragmatic choice for the purpose of object manipulation, since exact human-mirroring is not the emphasis.

The first challenge to be tackled was how to extract relevant information from the raw skeleton data. The skeletontracker_nu package was used to publish transforms provided by NITE as custom messages defined in the skeletonmsgs_nu package, on the /skeletons topic. The teleop node subscribes to this topic and uses the function get_key_user to determine the main user’s ID, based on their position in the depth camera’s field of view. Once the key user is found, looking up the relevant transforms becomes easy using a tf.TransformListener object.

The next major hurdle was to get the inverse kinematics working reliably, so that Baxter actually tracks the user’s hand motions. Firstly, the scaling factors in X, Y and Z for mapping a human’s hand position relative to their torso, to Baxter’s end-effector position relative to its base frame, were determined experimentally. By noting Baxter’s endpoint state at the outward limits of its reach in all three directions, and comparing that with a human’s arm measurements, I was able to find scaling factors that work well most of the time. Then I wrote the module ik_solver which utilizes Baxter’s IK Solver Service to find required joint angles to reach a desired endpoint pose. The solve method takes in the target end-effector position as a geometry_msgs.Point() and one of two end-effector orientations as a string (‘FRONT’ or ‘DOWN’, corresponding to front facing or down facing gripper orientations respectively). Since the skeleton tracker does not accurately detect wrist orientation, it is futile to solve IK for a continuous spectrum of orientations. Instead the two most useful ones for object manipulation are used, which the user can switch between by tilting their handheld controllers (PS3 or Wiimotes) accordingly. A horizontal controller signals ‘FRONT’ while a vertical one signals ‘DOWN’ to solve. Then the service request with this target pose is sent, and if a valid solution is found, the solution attribute (which holds a dictionary of joint angles) is updated. If at first a valid solution is not found, the IK solver is seeded with random noise for each of the limb’s 7 joints, and this repeats for 50 iterations unless a valid solution is found.

Now I was able to command Baxter to move each of its joints to track a user’s hand motions, but there were two big problems:

- The resulting motion was very jerky and unstable

- If one arm took a long time to find a valid solution, the other arm was having to needlessly wait for the 50 iterations to get over

The first problem was because I was using the position control mode for the arms, so I switched to velocity control to achieve smoother motions. I implemented a rospy.Timer to perform velocity control at a frequency much higher than the skeleton callback. For this Timer’s callback, which creates the control signal (velocity command) and moves both arms, a simple proportional control combined with an error saturation deadband immediately showed much better results. The arm motion was now smooth, and would not jitter when the user was not moving his hands.

The second problem was occurring because I was solving IK for both arms from the same callback, which meant they were being processed serially. To parrallelize this in order to speed up the robot’s response, I created separate callbacks for each arm, and ROS automatically creates separate threads for them (which is not a problem because both processes are completely independent).

Now the system was performing good. But Baxter’s IK Service still left me at the whim of solutions it found, without me having any control over selecting the best solution. This sometimes resulted in unnecessarily long winded motions to get to a nearby point:

So I replaced it with my own IK solver. The inverse kinematics routine I implemented runs multivariate optimization of a squared error objective function over the domain of forward kinematics solutions (joint configurations). Only the first 6 joint angles are considered, since the last joint angle (wrist roll) doesn’t really matter here. The joint angle 6-vectors are bounded by their physical limits. The objective function consists of two costs:

- Square of the distance between the end-effector position arrived at via forward kinematics, and the target end-effector position determined from skeleton tracking. This cost is most important, so has higher weight multiplied to it.

- Square of the L2 norm of difference between the current actual joint configuration and the joint configuration being evaluated by the optimizer (the guess). This is of secondary importance, so has lower weight.

The two weights are global variables that can be changed in the beginning of new_limb_mover.py. Additionally, to aid the optimizer, I provide it the Jacobian of the above objective function.

Finally the Wiimote features were added to the system, after which the user was able to open and close Baxter’s grippers by pressing buttons on the controller, and switch between the two gripper orientations by tilting the controller. This enabled the user to pick and place objects in Baxter’s vicinity. The Wiimote also provides vibration feedback to the user when the gripper grabs an object.

Future Steps

- The approximate average scaling factors to map human arms to Baxter arms should be replaced by accurate values specific to each user. This can be achieved by incorporating a quick calibration routine on start-up, which uses the skeleton data to measure the user’s arm length.

- For a truly immersive and natural teleoperation experience, wherein the user would be able to see, feel, and manipulate objects in the robot’s surroundings, we need to leverage VR technology. Integrating this system with a VR headset, and a camera mounted on Baxter would further enhance the human-in-the-loop aspect. My ultimate vision for this project is to have an embodied human-robot interaction so immersive and reliable, that the user may actually feel that they are the robot, at least for a moment.

Project Dependencies:

Project Details

Date: Mar 1, 2016

Categories: project

Website: https://github.com/tanay-bits/baxter_skeletonteleop